Sing With Me

I won’t sing this song of grief and hope just to turn my back on the way the world could be.

“To express myself without words, to paint my voice is a huge part of my identity,” musician and composer Sirintip told me last year when I decided to interview the singers in my life.

I also asked a fellow singer Caroline Mulvaney, If you had to explain why you sing, what would you say?

“Honestly, you know what I think it is? It just is a natural, human thing,” replied Caroline. “Every person on the planet is probably born with the urge to sing or make noise… I think society pushes that down. I used to be like that — I didn’t make a peep as if you shouldn’t sing unless you’re already a pop star.”

Caroline added, “I wish people just sang a little bit more, like hummed in the grocery store. I wish people were less afraid to do that.”

I asked Kristy Bissell, who is a senior voice teacher associate at New York Vocal Coaching as well as a friend and mentor to me, how does singing relate to your identity?

Kristy answered, “It’s the only thing that I’ve ever wanted to do with my life. It’s always been singing, ever since I was little. For some reason at the age of 4 or 5, I got so into The Little Mermaid. I learned how to sing from that movie.”

I rewatched The Little Mermaid recently. I relate to Ariel, a misunderstood daughter who gets taken advantage of by the villain Ursula, after her dad drives Ariel further away by bashing and destroying her precious collection of items from the human world on the surface. Ariel is fearless and vivacious, passionate and kind, but one of her most prominent traits is her curiosity. She senses intuitively that there is something important waiting for her up on that shore. When she saves Prince Eric from drowning, her dad scolds her for saving a human. Yes, her dad has genuine concerns about Ariel’s safety, but until the end of the movie, he refuses to see how he was asking Ariel to deny a crucial part of her identity. It’s not that under the sea isn’t a wonderful place to be, but rather it’s that Ariel has already seen it, lived under sea. To stay and be the perfect daughter for her dad would mean disconnecting from what her curiosity, intuition, and heart all communicated to her so clearly.

After watching the movie again, I wrote to my therapist:

It all worked out in the end for Ariel and it’s hard because I relate to Ariel yet I know that in real life, it doesn’t always just work out. In the movie, her dad, Sebastian, and all the naysayers support Ariel when she marries Eric. In fact, it is her dad who brings her legs back, allowing Ariel to walk on the shore with Eric after Ursula is defeated. In real life, abusers like Ursula don’t usually die in one swoop the same night they obtained the apex of their power. And when abusers die, their victims aren’t immediately freed like in the movie. Those wounds are deep and require people to actually find support and information to break free from the abuse mentally. I know that there’s no other path for me but the one I am on. I guess it’s just that I don’t know what to do with the doubt — what if I never get to feel better?

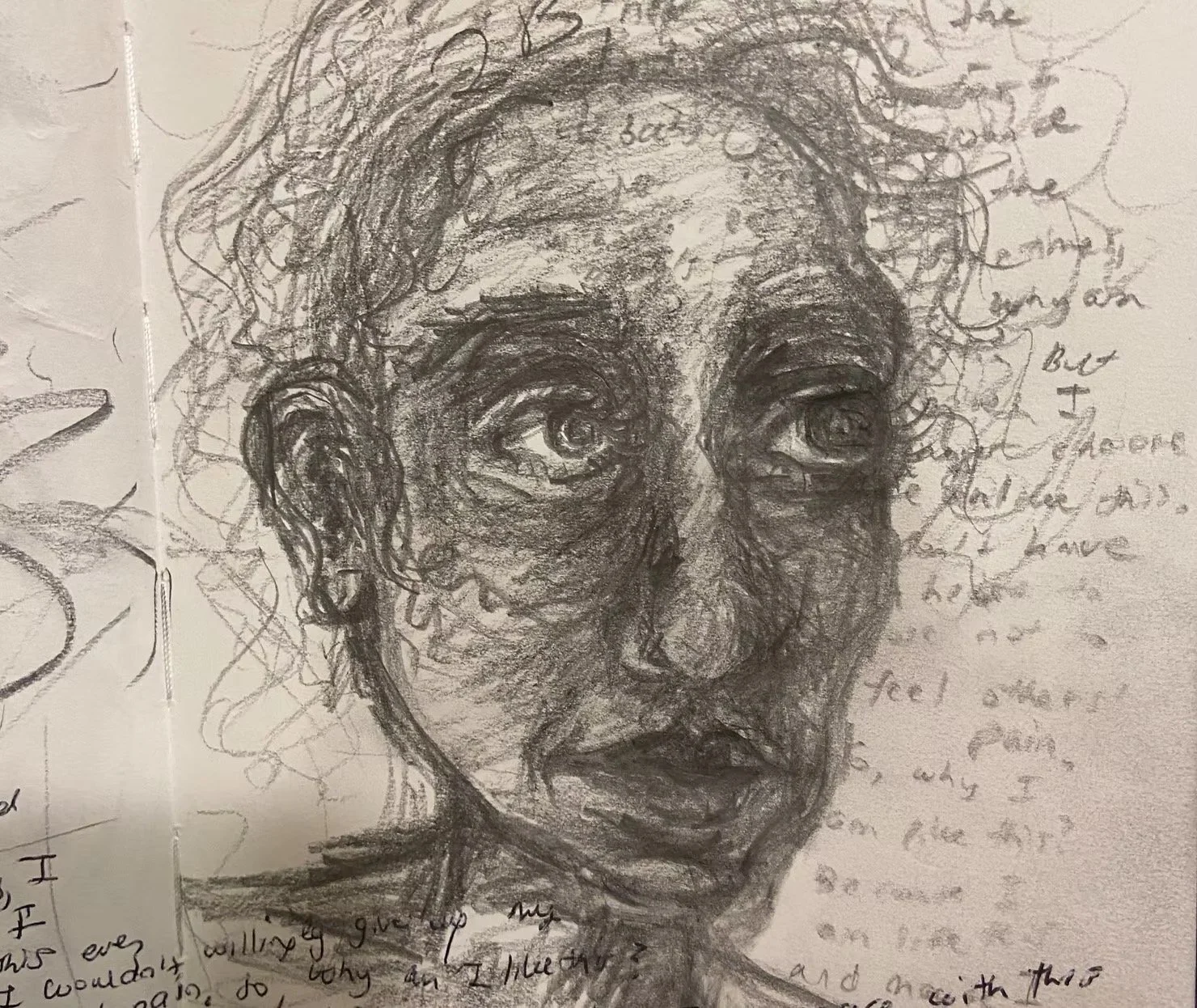

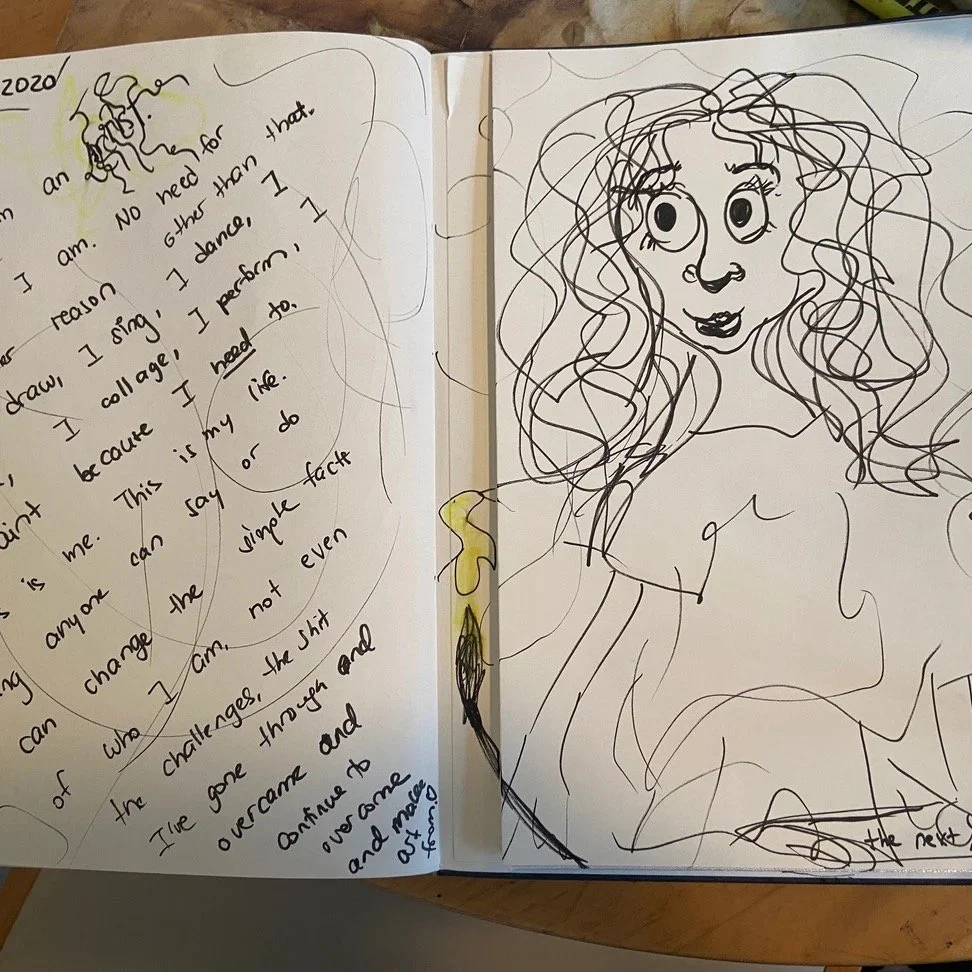

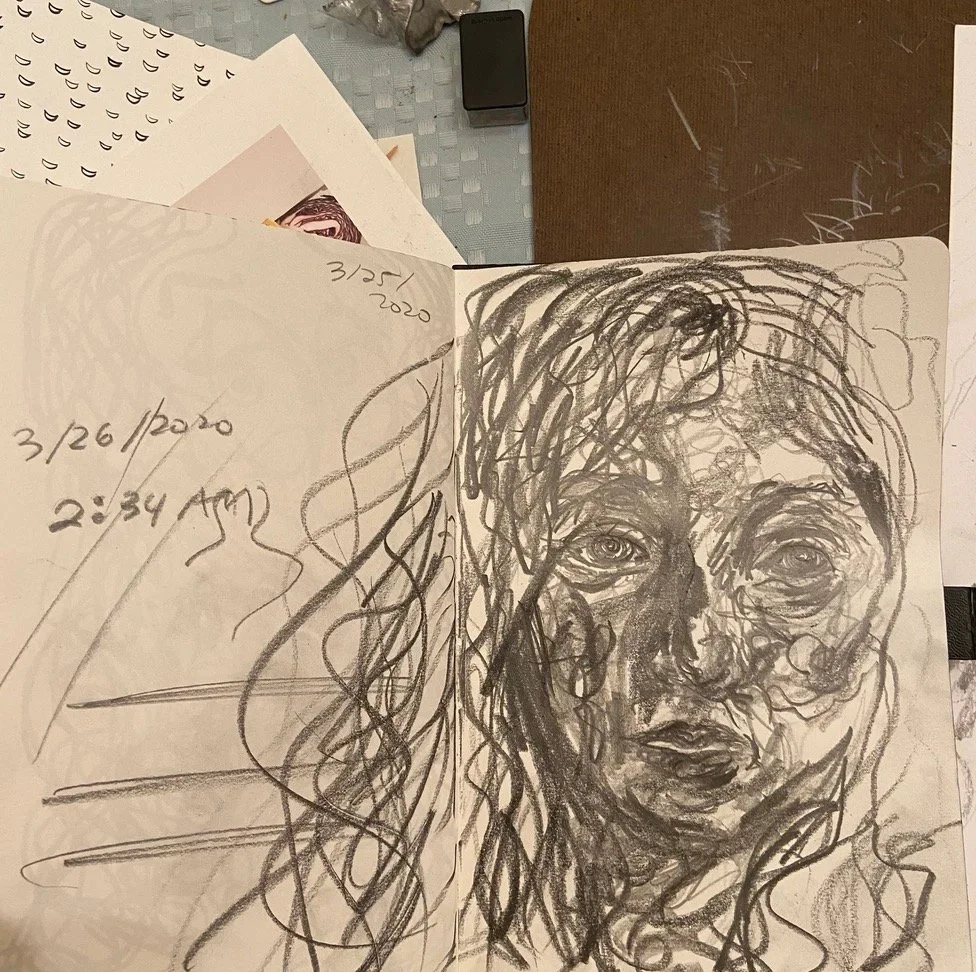

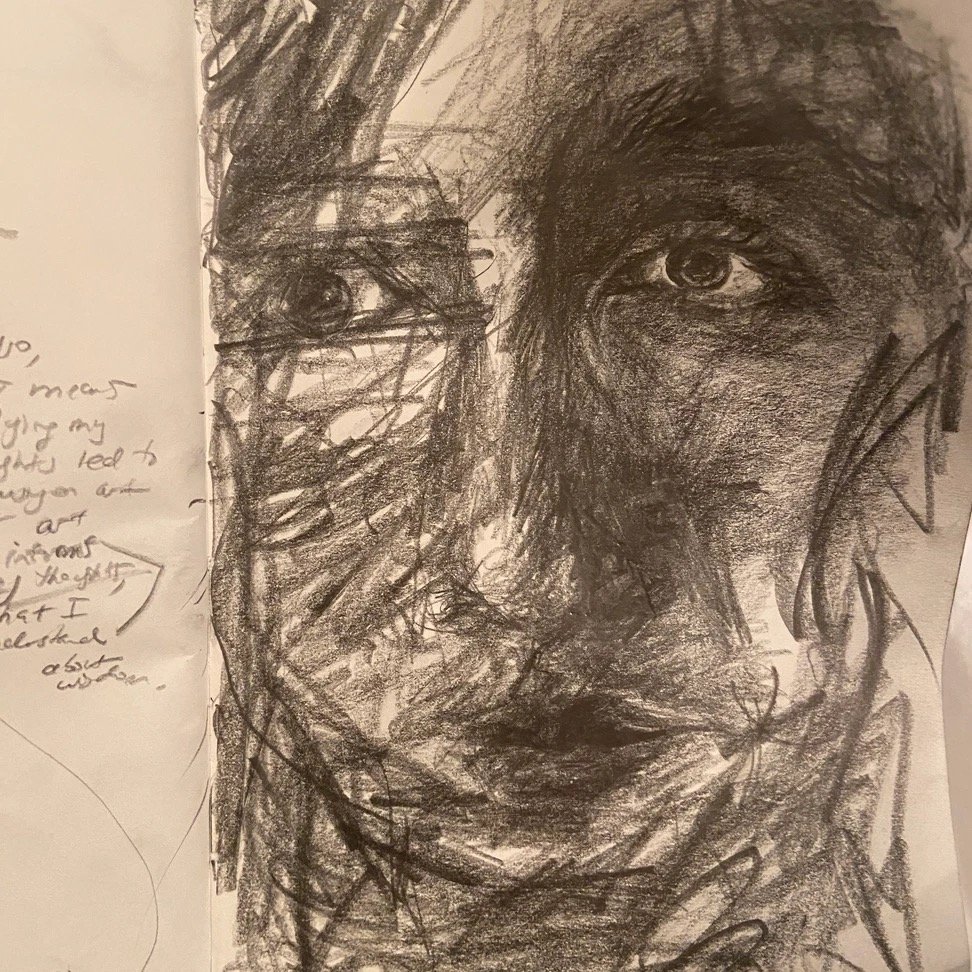

This is a story I’ve been trying to write for a while. It’s a story of how singing, physically using my voice, has aligned with my healing process. It’s a story of hours upon hours of pouring my soul into the air molecules of my room, my fingers dancing on the keys and with guitar strings. There have been times I processed a segment of my past trauma in therapy for complex PTSD and afterward, I felt a shift in my body, like a new part of my voice had opened up, seemingly all of the sudden.

“There’s so much science to back up why music is so healing,” Kristy told me in our interview. “It’s a universal language. If you’re feeling something, you put an album on. It can change our mood or reaffirm what we’re feeling. There’s an album for everything.”

Kristy shared with me that singing has given her confidence, empathy, and made her a better listener. “Singer would be one of the first things I would say about myself. I truly believe that I would have done it even if I wasn’t good at it,” she said.

“I feel safe singing…There were so many times I didn’t know how to express myself. My emotions outrun my words a lot. It helps me to communicate the way I need to.” She added, “I do have a learning disability, and that didn’t come through in music. It felt so good.”

I asked in my interviews with Sirintip and Kristy last year, You’ve talked about how no two people have the same voice. How do you believe this biological fact relates to our identities and how we see ourselves?

“Oof, that’s a deep question,” Sirintip said. “I definitely think it’s all connected. Being more comfortable in your voice [is] connected to being comfortable in your body and vice versa.”

Kristy answered, “A fingerprint is extremely identifiable, but the specificity of people’s voices — there are no two alike…There are people who are not in touch with their identity and music can help you do that. Music forces you to [explore your identity] even when it’s painful.”

Sirintip expressed a similar sentiment, telling me, “I have a lot of students who have difficulty expressing certain emotions in music. For me belting is about the intent, calling, but maybe some students haven’t been loud in real life and aren’t comfortable speaking loud, for cultural reasons or if they have family members who have told them not to be loud.”

She continued, “Or, they may have trouble expressing anger. I’ve given homework to students to throw things and connect with the emotion.”

In Kristy’s words, “A violin is a violin. A piano is a piano. A voice is a human being. Sometimes people want me to talk to them like an instrument, but there’s heart and soul to it too.”

When I moved back home to Queens just before the COVID-19 pandemic hit New York City, I was confronted with the facts of not only how my parents treated me as an adult, but also how they’ve treated me all along. I retreated to my room often during the early days of the pandemic, tapping the keyboard or strumming my guitar, all the while improvising lyrics with my voice.

I tried to share my voice and newfound love for making music with my parents. My mom and dad laughed at me. I tried to sing to my dad, but he didn’t want to hear me. I wrote a song about something my dad said (what he said? I don’t remember. I remember the hurt though). In my room, I sang out my lyrics:

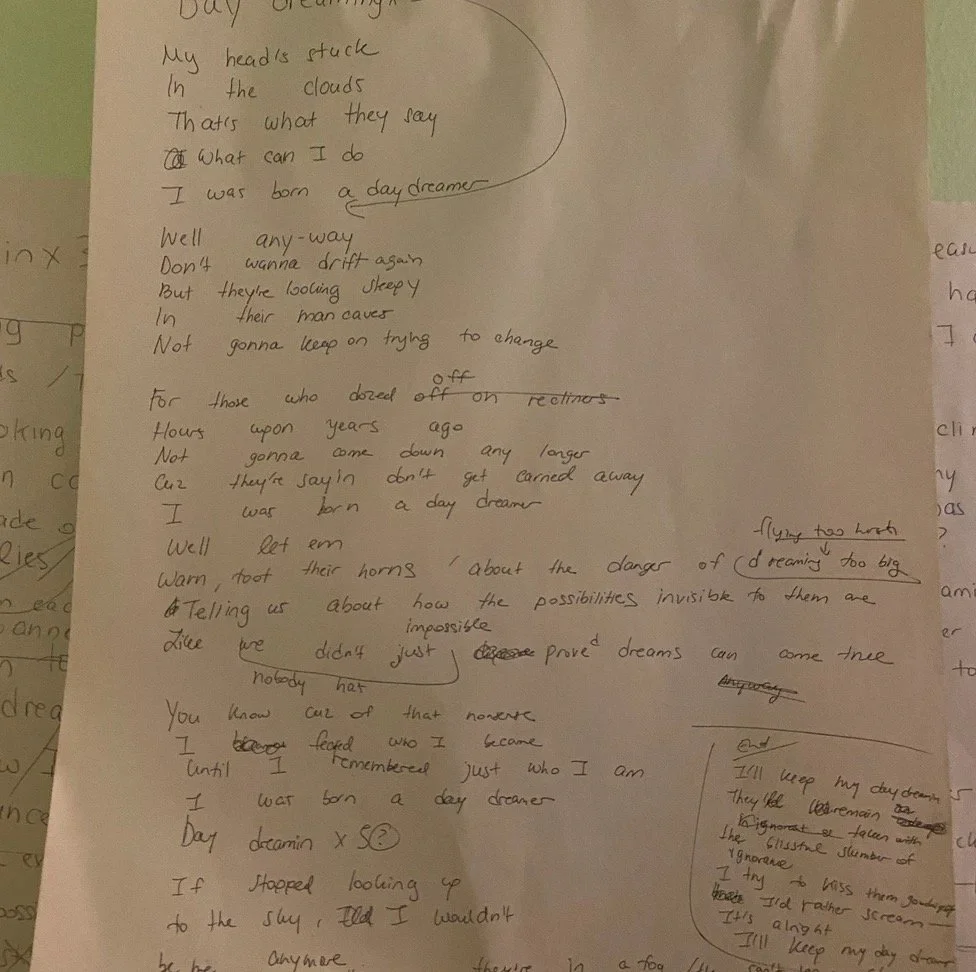

My head’s in the clouds, that’s what you say. Well you’re looking pretty sleepy in your man cave. Hey don’t wanna drift again, stop shaking your head. I’m tired of trying to change, this is how I use my brain. Day dreamin’ day dreamin’ day dreamin’... Dreamer wasn’t an insult, not until you came around. In a fog yourself, you yell that I gotta come down. Your nonsense made me afraid of who I became. Until I realized I prove you wrong every day. Racking my mind, how did they get this way? Tooting every horn they can find, warning about the dangers of flying too high, too high, too high. If I stopped looking up to the sky, I ask, who would I be? Not me, not me, not me. Don’t want to know, not for the sake of those who dozed off hours upon years ago.

And I sang to my mom and she said, “Can’t you sing without your face like that?” She was referring to the emotion that showed on my face because I felt the music. I feel the music. It runs deep in my soul, all through my veins, rushing through every molecule of my body.

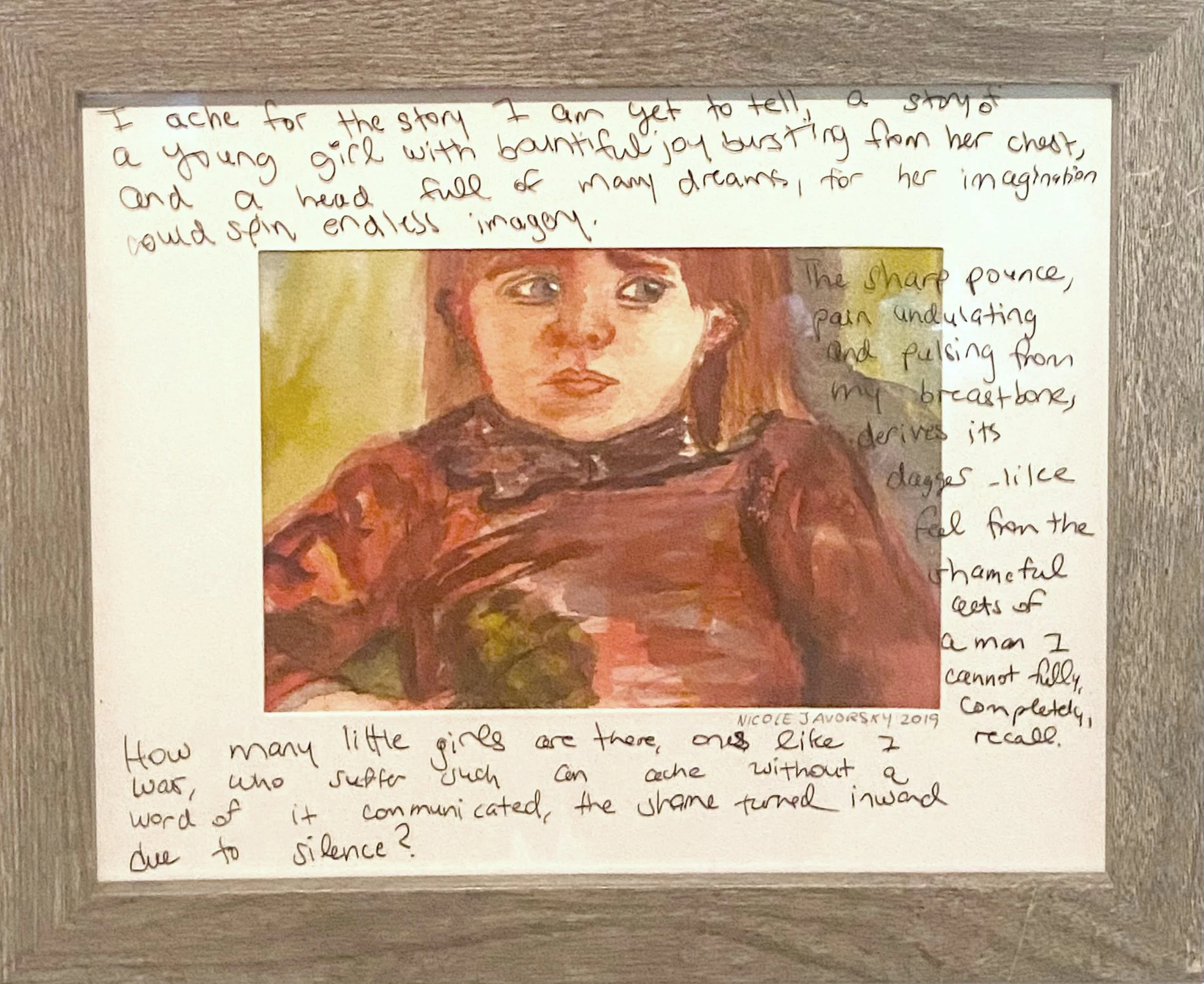

Kristy gave me a compliment when she told me that I’m one of the most expressive singers she knows. I don’t think I ever shared with her that my mom’s first reaction was to treat my facial expression with contempt, skepticism, and disdain. There are a lot of things I haven’t said about my parents, how I used to hide in my closet as a kid. I don’t know what to make of the fact that the place where my gym teacher sexually abused, physically assaulted, and threatened me was also a closet, except at school instead of at home. At every step of the way, my parents looked the other way. They explained away my bruises, and brushed under the rug my nightmares, developmentally regressive behaviors I hadn’t shown before, my difficulty staying asleep, and sudden trouble sleeping alone.

During the pandemic, I walked by my elementary school, across the street from the apartment building where I grew up and lived in once again until the following fall when I moved to Brooklyn to be on my own again, to escape my parents and the constant reminders of my trauma everywhere I looked. I wrote this poem standing outside the school where I endured horrific abuse by my teacher —

The ribbons inscribed with my dreams

Are tied on the loops of this fence

Around the building

I stand here so still and tall

At the entrance

Waiting for nothing

“She, I, learned to fear our wild ways”

Watercolor on paper, waterproof ink on frame. 9.5 x 11.5 inches. 2022.

I wandered into a small cafe on a still afternoon last summer. When I ordered at the counter, I noticed the cashier was a young girl, maybe 10 years old, the same age I was when my gym teacher was abusing me in a closet at my elementary school.

Later while I was seated at the table, I heard her father enter and scream at the girl who had been talking with her little sister, “Stay apart from your sister! Can’t you just be separated for a moment?!”

I continue this story with the poem I wrote just after exiting the shop —

Divide and conquer

That’s what they say I guess

But I wish we can all embrace connectedness

Togetherness

Upon hearing all the fuss

The cafe patrons rushed out all at once

I lingered a moment longer struggling to see

What I could do if there was something

I came up with nothing but a weak goodbye to

The younger daughter

Before I left I heard her state her anger at a

Whisper

No one else heard her but they heard her father

Kids the saying goes should be seen and not heard

But I wish the whole cafe could’ve listened to the

Quiet rage of this child

And heard her

I wish they heard her

I wish they heard her

We should have heard her

This week, I saw the Broadway musical Hadestown. In the musical, the character Orpheus sings, “If it's true what they say, I'll be on my way. But who are they to say what the truth is anyway? 'Cause the ones who tell the lies are the solemnest to swear. And the ones who load the dice always say the toss is fair.”

He continues, “And no answer will be heard to the question no one asks. So I'm askin' if it's true, I'm askin' me and you and you and you.”

In Hadestown’s telling of the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, King Hades agrees to let Orpheus’s beloved Eurydice go, along with the others in hell who wanted to follow Orpheus. However, Hades includes the stipulation that they travel in the cold and dark single-file, not hand in hand. A deal is made, and if at any point during the journey Orpheus turns around to check if his love is still right behind him, Eurydice and the rest will be sent right back to Hadestown. Orpheus and the others travel a long, lonely way just like this, but ultimately, he fails to bring his love Eurydice back from hell because he becomes overtaken with his own doubt and fear. Orpheus is plagued by his thoughts, Is this a trap? Why would she travel all this way with me? What if she is already gone? And steps away from the finish line, Orpheus turns around. Watching in the audience, I couldn’t help but freeze in disbelief. No! He was so close! Yes, he was so close and regardless, we in the audience must watch as Eurydice sinks back into hell, and must witness the looks of devastation, shock, and powerlessness wash over the faces of Orpheus and Eurydice.

King Hades’ stipulation is based on a weapon common to abusers and oppressors — divide and conquer. Self-doubt festers easily when there is no one to witness you, no one to walk with you, no one to squeeze your hand when you fear your demons will overtake you. Hermes, one of the other characters, references this phenomenon when he talks about how we fear the bulldog aggressively bearing his teeth, but the threat of the bulldog is upfront, clearly visible, known. Doubt, on the other hand, is often a greater threat because it invades the psyche, weakens the strength of hope, and can ravage the foundation of our will to continue pursuing a path we used to know intense dedication toward. King Hades’ “divide and conquer” stipulation creates an even more fertile breeding ground for doubt along an already challenging journey. Yet, it is Orpheus who fails to see through King Hades’ stipulation and grasp its purpose.

Turning around, of course, does not have a logical purpose. If he had turned to see Eurydice gone, turning around could not change that fact. And turning around to see Eurydice would only lead to losing Eurydice for good. Orpheus, then, turns around not because it can lead to anything better or good, but rather because he cannot stand his doubts any longer. He turns around to satisfy his ache to know, and of course, this action only worsens the pain because it destroys the hope that had been there all along, eclipsed by doubt but nonetheless there inside of Orpheus.

My story isn’t as rare as most of us would like to believe, myself included. This is why I share my story and why I will never stop using my voice. The lesson of Orpheus’s tragic tale is why I sing about what I’ve experienced and my healing process. It’s why I share the vulnerable truths behind my art. And after all, it wasn’t just my teacher’s physical and sexual abuse that silenced me. It was also his words. He used his voice to confuse me and threaten me. He manipulated me.

Manipulation and emotional abuse doesn’t always appear cruel on the surface of a single remark. But imagine the impact of years of “advice,” subtle denials of who you are, subtle disrespect and being on the receiving end of a perpetual stream of comments doubting your choices, mixed with moments of rage, guilt tripping, and other manipulation tactics. All this, too often in an environment we were born into. It can be extremely difficult to identify a pattern that originated in childhood or during a traumatic period of adulthood, or maybe even started generations before our births.

Seeing isn’t done with merely our eyes. It’s where we look, how we listen, where we go, what we feel, how we notice. I write about my experiences of being abused because I want to help others see the layers of reality that it can be easy to bury deep within us or turn our heads away from — whether it’s the pain behind our own actions, the ways we stay quiet to appease others, or something else.

Too many of us have been silenced and might not be fully aware of it yet, but we don’t have to stay quiet. As Kristy put it, “Singing songs is the opposite of being silenced.” We don’t have to keep turning our heads away from painful truths, and I don’t want to end up like Orpheus. I won’t sing this song of grief and hope just to turn my back on the way the world could be. Take my hand so I do not have to walk alone. Sing with me.